|

| Sea+mere = large lake |

For this week's Five on Friday (to join in with Amy at Love Made My Home) I'm going to take a look at a few place names to show you how to get more out of your travels. As we drive along even the swiftest motorway we see signs for all kinds of places that we've never been and are never likely to visit. But we can probably glean some information about them - just from those signs.

(Don't assume the photos match the text!)

|

| Streetview snip |

Let's start with one of my favourites. Driving along the A64 through North Yorkshire, near Malton, you'll pass a sign for Huttons Ambo. There are lots of places in England called Hutton but, as far as I know, only one Huttons. There's a reason for that. Hutton comes from two Old English words, hoh and tun meaning a hill spur and a farmstead. Hence Hutton is a farmstead near a hill spur. Now, if you drive along the side road that's signposted Huttons Ambo you will find High Hutton and Low Hutton but you'll never find the mythical Huttons Ambo, because it doesn't exist. Ambo is Latin for 'both', so the sign is directing you to 'both Huttons', rather than a single place.

Stiffkey

Of course you can't always tell much from the name as it appears today. Modern place names have been handed down for many years, In the case of some towns that existed in Roman times that can be as long as 2,000 years. One of the earliest written records of English places was the Domesday Book; a survey of towns and villages carried out on the orders of William the Conquerer in 1086, very shortly after he won the Battle of Hastings. He wanted to know exactly how many people he now ruled and exactly what they were worth (for tax purposes). Domesday is a useful, although sometimes misleading, source about place names. On the other hand it can be surprisingly enlightening.

Over the intervening period the pronunciation of place names can have changed dramatically, and their spelling has often changed beyond recognition. Take Stiffkey, for example, on the Norfolk coast. How would you pronounce it? I'm willing to bet you'd be wrong! Domesday lists it as Stiuekai, which is much more like what the locals call it today - Stukey. On the other hand, the actual word comes from two Old English terms styfic and eg, meaning an island in a marsh, with tree stumps. (Now try the nearby town of Happisburgh and see how long it takes you to come up with the modern pronunciation of Hazebruh. No, I don't understand either!)

|

| Skarthi's Burh |

A note for my Transatlantic readers. There are lots of towns that end with the suffix -borough in the UK. Please note, they are not pronounced 'borrow'. Borough (and similar endings like Edin-burgh) are all pronounced 'bruh' like the first syllable of brother. There's a reason for that. It's because all those endings come from an Old English word burh, meaning a stronghold or fortified town. The first half of the name then tells you something else about the place. In Scarborough's case it's the name of the guy who founded it - one Skarthi (sometimes written Skardi because of the nordic rune 'thorn' that looks like d but is pronounced th) who was the Viking lord who turned up in 966 and established a settlement there. Previously it had been the site of a Roman signal station, but Skarthi's Burh was the first town. There are other 'borough' towns, such as Boroughbridge, where the etymology is obvious, but beware. Borough Green, for example, is thought to stem from beorg, meaning hill.

Breedon on the Hill

|

| The church, Breedon on the Hill |

Now imagine a Saxon settler wandering through the land that would later be known as Leicestershire and spotting a high hill that looks like a safe place to set up a village. The conversation possibly went a little like this.

Saxon: "Excuse me good man, what is the name of that fine cliff in the distance?"

Celt: "Bree"

Saxon: "Thank you, my woad-painted friend. I shall settle my village there and I shall call it Bree Hill."

(Or in his language, Bree Don, because that's the old Saxon word for hill.)

Many years later the village has become known as Breedon and map makers, to distinguish it from lots of other Breedons in the country, call it Breedon on the Hill - or Hill Hill on the Hill. You can't miss it. Just drive up the A42 through Leicestershire and you'll see it without any trouble at all. (Of course the village is actually at the BOTTOM of the hill because it's too steep to make living at the top workable. Only the church is at the top.)

|

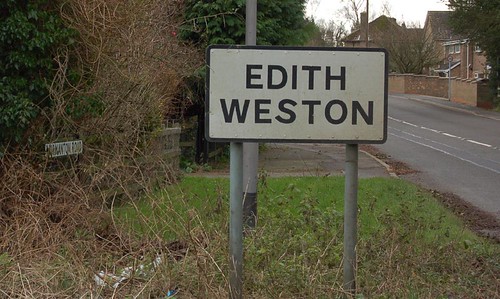

| West farmstead owned by Queen Edith. (Wife of Ed the Confessor) |

So how can I round this up? There are so many different place names, and so many reasons for those names, that limiting myself to just five is almost impossible. I could pick another favourite at random. Marsh Gibbon sounds exotic, doesn't it? But actually it just means marshy land owned by the Gibwen family. Higham Ferrers? Main (high) enclosure (ham) belonging to the Ferrers family. You'll find such manorial suffixes all over the country. Many of them are French-sounding. That's because the people who first wrote down the names in any meaningful way were French Normans, remember? Domesday and all that. Of course, the previous names were often possessive too. Goadby Marwood, for example, means farmstead of a man called Goadi, now owned by the Marwood family.

So now you know. Next time you go on a journey take note of any interesting places you spot, then see if you can find out how they got their names. But first go visit Amy at Love Made My Home and see what other fives people have found for you this week.

References

*What's in a name? That which we call a rose. By any other name would smell as sweet. Shakespeare. Romeo and Juliet.

Huttons Ambo Village Website. http://huttonsambo.blogspot.co.uk/p/about-huttons-ambo.html

Mills, A. D. 1998 Dictionary of English Place-Names. Oxford University Press.